What is paste?

While diamonds last forever, they are expensive and relatively hard to come by, especially at greater sizes. The same goes for most other natural gemstones; they are demanding to find, and even if the quality of the stones is excellent, uniformity in colour and size can be an issue if you’re a jeweller making a piece of jewellery with several stones. Of course, some minerals are easier to come by and in general more uniform in colour, and certain mines may, if the colour of the mineral is caused by the presence of a particular element, provide good access to gems of the same shade. Still, the real deal is expensive, and back in the days, it was even more so. Consider for instance the great distances a stone has to travel from a mine in Sri Lanka to a jeweller in London, and how time consuming it was 200 years ago. South Africa, Australia and Brazil are currently providing us with diamonds, opals and tourmaline and amethyst respectively (oftentimes at a great cost to those extracting them from the earth), but before 1867, nobody was looking for diamonds in South Africa. Opals were first found in Australia in 1848, and before high quality amethysts were discovered in Brazil in the early 1800’s, good stones were fairly hard to come by, and prices high. Thus, there was a market for man-made replicas.

Today, we have synthetic versions of several gemstones, chemically identical to their natural counterparts, as well as several man-made materials simulating the brilliance of diamonds, like cubic zirconia, YAG and moissanite (itself a natural mineral, but a synthetic version is made to simulate diamonds). To our ancestors, however, the best alternative to the real deal was glass.

The invention of paste

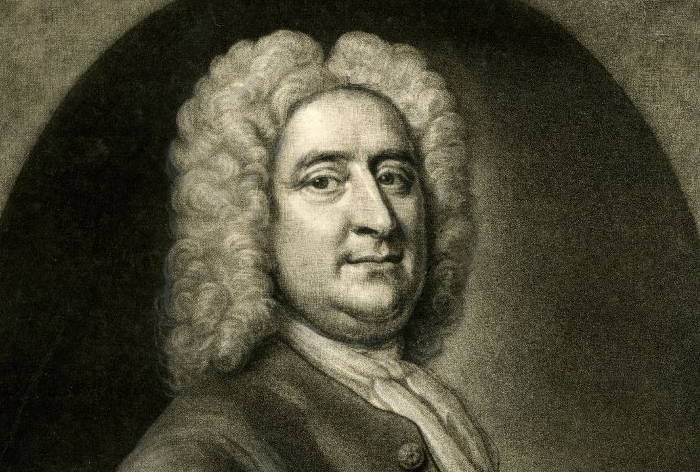

Glass comes in many different varieties, and just like you wouldn’t make a wine glass out of the same material as a window pane, the types of glass available in the 17th century were unsuitable to make faceted stones out of. Not only did the glass need to be extremely clear, bright and reflective, it also had to handle cutting and wear without breaking or chipping. George Ravenscroft (1618–1681) mixed flint, potash and lead oxide and was able to create the first modern lead glass in 1681. The lead increased the refractive index which basically made it sparkly, which is why this kind of glass is often referred to as (lead) crystal.

Ravenscroft’s work paved the way for the jeweller Georges Frédéric Strass (1701–1773) who was able to create glass that was soft enough for cutting without cracking, and in the 1730s he was using his false diamonds in his jewellery. Being a skilled artisan and well connected, he was able to market his product to the French royals, which in turn of course created a demand for it.

The magic of foil

Closed-back setting of stones was very common in the 18th century, and since that didn’t let any light shine through the stone, it was a common trick to put a piece of foil (transparent or coloured) behind the stone to make it pop or to make it look like something else – you could for instance add purple foil behind a faceted rock crystal to make it look like an amethyst. The same was done with paste, either to make them look more like diamonds or to make them look like coloured gemstones.

The rise and fall of paste

Paste became quite fashionable in the Georgian era, providing both value for money, security when travelling (if someone stole your paste jewellery, it wouldn’t mean the end of the world to you, and besides, it would make you a less attractive victim) and flexibility as jewellers could be more creative with this affordable material than they could with real gemstones. While the earliest paste would be set in gilt metal or silver, gold would soon be used instead. Basically, there was no shame in wearing paste.

The Victorians had however not the same tolerance for fake gemstones as the Georgians, and combined with the change from closed-back to open settings, which made foiling less of an option, the popularity of paste declined. That is however not to say that it fell out of use. Rather, it would not be considered a unique selling point anymore. More affordable jewellery would still be set with “fake gemstones” – i.e. paste, but the stones would be set in gilt metal or low carat gold, having no inherent value.

… and rise again?

Daniel Swarovski (1862–1956) was a Bohemian-born Austrian jeweller who developed an electric machine that could cut lead glass, thus turning the production of paste from a painstaking manual process to an automated one. He patented his creation in 1892 and opened a factory along with his two partners. The Swarovski brand and several other jewellers and fashion houses managed to make rhinestones fashionable again in the interwar period, finding a market for what is basically costume jewellery, but at a premium price.

Paste, rhinestones and strass

Rhinestones were originally stones (rock crystals) from the Rhine which were particularly sparkly, and foiled lead glass would look very much like them, which lead to the word being used as a synonym for paste. In modern day English, it has taken over, and is applied rather generously to anything and everything glass or plastic that emulates gemstones, including mass produced foiled flatbacks that only a less discerning 5 year old would think of as diamond-like. In many other languages, Georges Strass’ name would live on through “strass” being the word for paste.

Paste or the real deal?

Telling real from fake is fairly easy when it comes to paste if you’ve got the right equipment. A loupe will allow you to see the bubbles that will always be present in glass, even if they’re too small to catch with the naked eye. Being fairly soft (about 5.5 on Moh’s scale) glass scratches easily, and so visible scratches in a stone that looks like a real precious stone is a telltale sign of it being paste. On bigger pastes, you can also see that the facets seem almost “dull”, as in the picture of the big blue one above.

Isn’t lead dangerous?

Lead was used in all lead glass and crystal up until the 1920s, and so all antique paste will by definition contain lead. As with lead crystal used for serving and drinking, any surface lead will most likely be gone by now due to age, but acidity may release more lead (which is why you shouldn’t use your lead crystal glassware to serve orange juice), and our skin is slightly acidic. While not an expert on this (so do not sue me!) my advice would be to not chew or suck on any paste jewellery. All paste set in a closed-back setting will be fine as there will be no skin contact, and the same goes for dangly earrings and brooches.

Necklaces with several paste stones resting against your skin may not be good for daily wear, but just as you won’t get ill from drinking a glass of coke from a crystal wine glass every now and then, wearing jewellery with a possibility of leaking once a month is most likely perfectly harmless. If you are worried about lead, you can read more on testing for it in this article.

Sources

- Starting to collect antique jewellery by John Benjamin

- Antique and 20th Century Jewellery by Vivienne Becker

-

-

3 years

Tagged alloys, georgian, pinchbeck