Pinchbeck Jewellery

We all know that not all that glitters is gold, but some gold-like metal isn’t even gold plated or gold filled. Some of it is actually just plain brass.

Brass is an alloy made up of (mostly) zinc and copper, and there are tons of different alloys, including tombac, which I’ve written about previously. The proportion of the main metals as well as the inclusion of certain other metals will change both the look of the alloy and what it is suitable for.

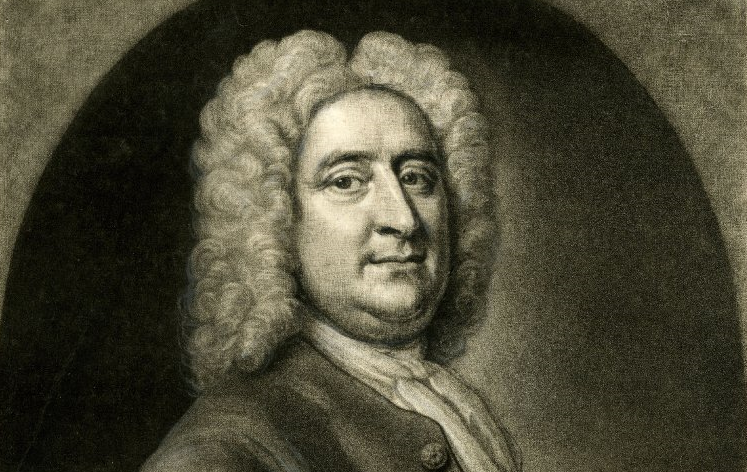

Pinchbeck is named after the watchmaker Christopher Pinchbeck (c. 1670-1732) who discovered the alloy. At the time, only 18 carat gold was allowed in Britain (and by extension, the future United States of America and all other colonies in the British empire) – you can read more about when different carats were introduced and removed here – and so gold was an expensive commodity. This, combined with pinchbeck looking very much like gold, made it an attractive alternative to the public, something which is evident in the care that was often put into the creation of pinchbeck jewellery. To the Georgian mind, “real” and “fake” didn’t carry the same meaning as it does to us today, and so there was no shame in wearing “fake” stones set in equally “fake” gold. Thus, a lot of the Georgian jewellery that has survived to this day (and that is not so exclusive that it is kept in museums and the private collections of the very affluent individuals) carry little material value. That is not to say that pinchbeck was deemed equal to gold – far from it, but there was no shame in adorning oneself in a good replica of the real deal.

Pinchbeck remained popular until lower carat gold was introduced in 1854, at which time 9 ct gold took over as the go-to material for fairly inexpensive jewellery.

Due to its rarity, age and the oftentimes impressive workmanship, surviving pinchbeck jewellery is quite popular with collectors, so if you find an appealing piece through at trusted seller, it could be an excellent investment!

-

-

3 years

Tagged gold